The 19th episode, wherein the ASCRIBEPodcast examines the difference between reality and imagination, in a story/essay hybrid that asks more questions than it answers, (like any good work of art should).

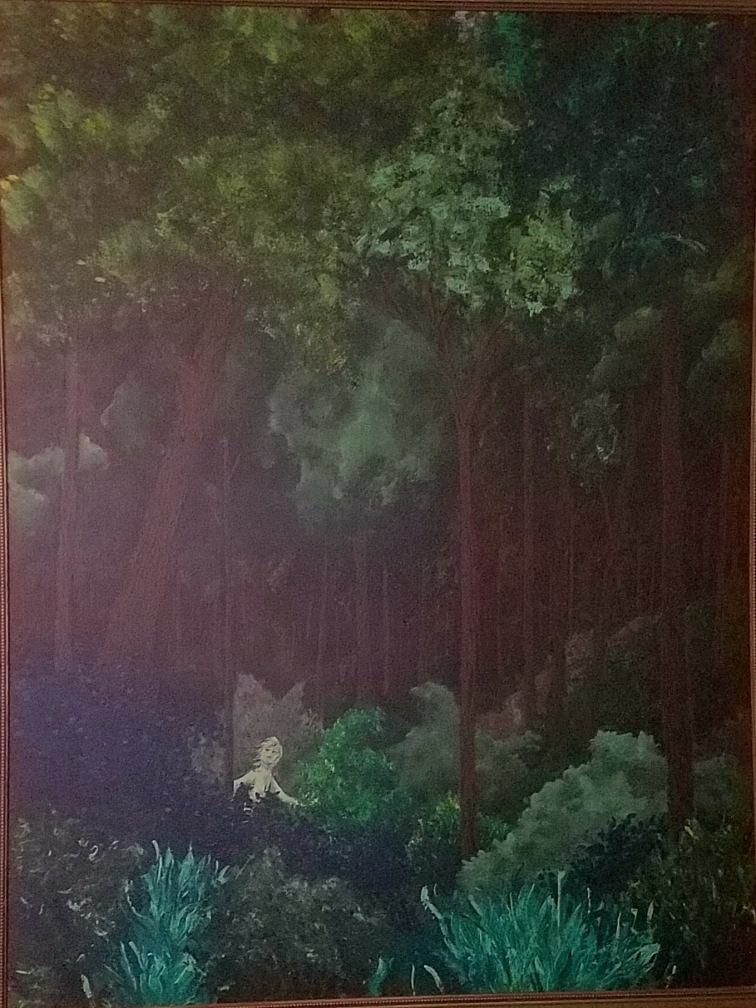

Inspired by this image:

STORY: The Painting

You weren’t supposed to see me.

Photographs have the ability to capture a split second of time, forever isolating and immortalizing a span too brief to be otherwise noted. They allow you to press pause, and carefully study tiny details that in the moment, would be invisible. What’s more, they don’t stop there, because after revealing these hidden secrets, they go on to claim sole ownership of truth, and forever after, our perception of a photograph is our perception of the reality it represents. An imperfect vessel, just like any other, distorting and shaping the memories that it holds.

Paintings, on the other hand, act differently. They remain as inadequate in exemplifying the totality of a moment, but on another level. Their focus is not a span so brief no one could take it in, but the state in and through which it was taken. Paintings are created and seen over time, and in their revision and revisitation often say more about the person making them than they do about their subject. They are a struggle to express ourselves, in spite of or embracing our limitations, to let others see how we feel, partially, through yet another broken lens.

So when I say that you weren’t supposed to see me, running through the middleground of the forest, making furtive eye contact as I attempted to once again disappear, you may perhaps not understand what I mean. If it had been a camera, and I was forever captured by a briefly unshuttered aperture, no one would have thought twice. They would have gaped. They would have stared. They would have come looking for me. There would have been proof, indisputable evidence, that I had been found, if only for the briefest possible period of time. Yet, as I caught myself looking, not into the lens of a camera, but the eye of a painter, I knew that my immortalization would have a very different effect.

I stopped, for no more than two or three seconds, but I’m sure to the artist it must have felt like an eternity. I know that I scared him, because in the finished work I look like a ghost, which, as stated, echoes the artist’s fertile mind more than my own appearance. The way that the trees loom, unending, uncaring, almost sinister in their ambivalence says something too about the moment. I wasn’t supposed to be there. And you aren’t supposed to care.

Most people who saw merely shrugged it off. They asked each other what it meant as they passed by, not really looking for an answer as much as the opportunity to sound like they “got it.” Art is weird that way. It means something different to each partaker, colored subtly by whatever tinted glasses of nostalgia and experience they bring to the proverbial table. Art is, at best, a collaborative metaphor; a bond, between creator and audience, to make something out of something else, however unwillingly it is entered into by either party.

So no one came looking for the boy in the woods. The boy who wasn’t supposed to be there. The boy who was running; and while running, stumbled into a painter’s frame for the briefest possible moment, and also, for time immemorial, until rust and dust and imperfect memory complete the obliterations they long since began. The boy who was running from something, and hiding from everything, including perhaps, himself. The boy who found himself found like a mirage in the desert, that reveals more about the weary travelers thirst than the unchanging sands in which he is entombed.

The boy who might have been only a figment of a painters imagination. A trick of the light, a misshapen shadow. A terrifying look into the taught darkness where any mind might slip with the slightest provocation.

If it had been a photograph, someone, somewhere, would have taken, if not myself, at least the photographer seriously. His picture would have captured something that was really there, briefly, whoever, whatever it was, and it wouldn’t have been his fault. Whether it was the gaunt figure of a runaway, or a blurred mote of light caused by an unsteady hand, people would have known that it was “true.” Even as their version of a moment in which they were not present was roughly handled by a contextless exposure of undeveloped film.

But I did not see a man with a camera. I saw a man with an easel. A man who had to choose what he saw, making himself the responsible party, and over the course of several weeks, fight a battle between his own mind and frustratingly limited abilities to convey a larger picture. What was it like in those woods? What did I see? Am I crazy? Did I imagine it? What does it all mean?

You weren’t supposed to see me. And neither was the painter.